Participating in a project as a federal subcontractor can be very lucrative — but as in any construction contract, you need to thoroughly understand your rights as well as the rules and requirements, especially those that concern your ability to collect and receive timely and complete payments. If you have extensive experience in private contracting, don’t get complacent. Getting paid in full and on time as a federal subcontractor is a challenge that’s different from when working on private projects.

You cannot sue the government or put a lien on a federal facility in case of non-payment. Under the Contract Disputes Act, the government has no immunity in disagreements involving Prime Contractors but not subcontractors.

The legal recourse commonly available to subcontractors for private projects is not the same in public works.

However, there is legislation that can help federal subcontractors should you encounter payment issues: The Miller Act.

The Miller Act provides a way for subcontractors to recover unpaid earnings on federal projects. Subcontractors go into business with Prime Contractors or higher tier federal subcontractors, and there are cases where subcontractors do not get paid for a multitude of reasons.

As a law, the Miller Act (40 United States Code Section 3131-3134) requires contract surety bonds on all federal construction projects.

Before a Prime Contractor can hire a subcontractor for alterations, repair, or improvements costing upwards of $100,000 on a public building or structure, the Prime Contractor must post a payment bond and a performance bond that cover all labor and materials to the Government first.

The Miller Act also prohibits Prime Contractors from waiving a federal subcontractors’ payment bond rights before the beginning of the project.

Subcontractors who have not been paid can pursue civil action to recover payments through the Miller Act.

It’s important to note that the Miller Act covers all U.S. subcontractors.

Many states have their adaptations on the state level as well, called “Little Miller Acts.”

The payment bond posted by the Prime Contractor is for the benefit of subcontractors. It is a guarantee that subcontractors will receive payment for the services and supplies they’ve rendered.

The performance bond is for the benefit of the federal agency or public entity that hired the Prime Contractor. The performance bond guarantees that the Prime Contractor will perform and complete the project in accordance with the contract.

The Miller Act requires both bonds to be posted by the Prime Contractor. The Act was created to protect subcontractors, specifically first- and second-tier subcontractors. Federal subcontractors lower than the second tier cannot use the Miller Act to recover payment.

✓✓✓ The Miller Act is only for federal construction projects. Subcontractors are not protected by the Miller Act when they enter private projects, commercial projects, or state and local projects. If you’re encountering a payment issue as a subcontractor in a contract that is not part of a federal project, you cannot use the Miller Act.

✓✓✓ The Miller Act is only for federal subcontractors. Prime Contractors cannot use the Miller Act to make a payment claim. Since Prime Contractors are hired directly by the government through a binding contract, they have the option to pursue legal action based on the project contract. The rules are entirely different in that case, and it’s best to enlist legal assistance to discuss filing a suit against the government.

✓✓✓ The Miller Act only covers first and second tier federal subcontractors, including suppliers. The top tier is the Prime Contractor. The Miller Act only covers up to two levels below the Prime Contractor.

Are you ready to make a Miller Act claim? We can help.

Here is an overview of the subcontractor rights guaranteed by the Miller Act:

While the Miller Act strictly protects the rights of federal subcontractors to full payment, it is still a legal proceeding that would require facts and evidence. Absolutely make sure to keep a detailed record of all the receipts and financial records related to the costs incurred for the project. Here is the list of covered costs under the Miller Act:

Mechanics liens do not apply to public projects, but the Miller Act practically allows subcontractors to make a claim against the payment bond as a direct substitute of the federal property. Subcontractors can make a claim directly against the payment bond and subsequently receive the money if the claim is successful.

The surety that holds the bond will investigate the claim (as is wont to be done in their interest) and request further information. When the claim is verified, it will be paid through the bonding company/surety or the prime contractor.

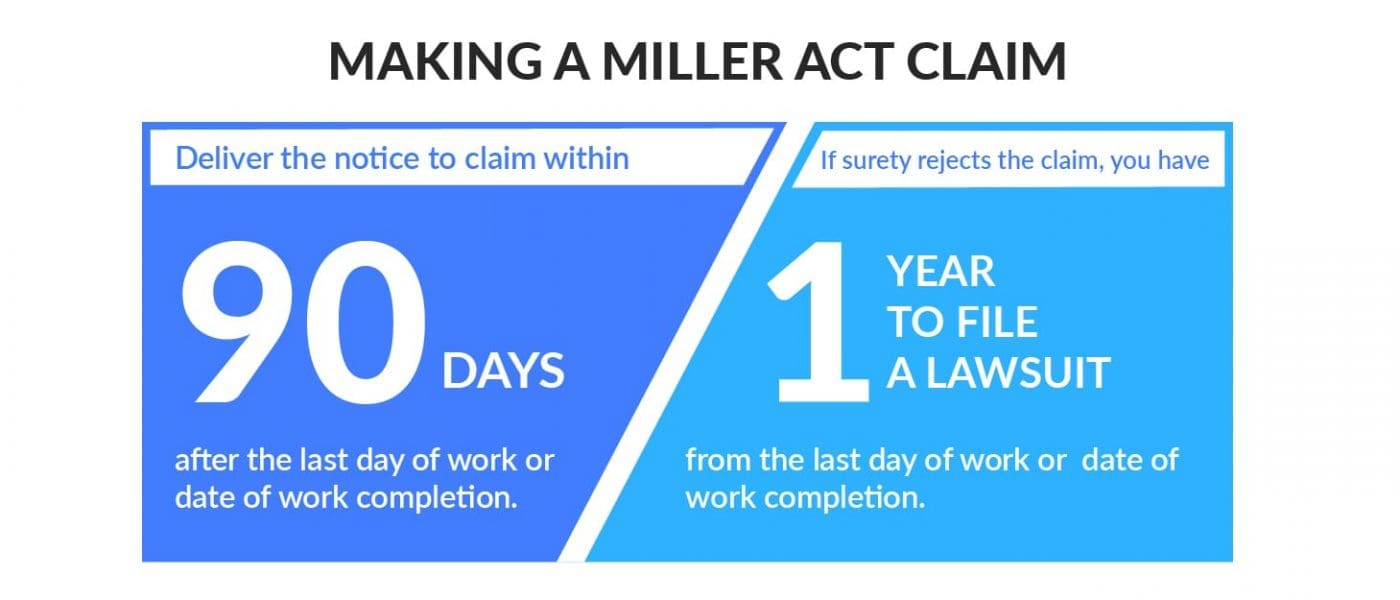

Another difference between the mechanics liens and Miller Act claims is that subcontractors don’t need to deliver a Preliminary Notice to be eligible to file a claim against the bond. The main requirement is for the subcontractor (claimant) to file their claim within 90 days after the last day of work or supply delivery.

If you’re a first or second-tier subcontractor who hasn’t been paid in full, you qualify for a Miller Act claim as long as 90 days haven’t passed since the last day of work or supply delivery to the federal construction site.

Qualified? Here’s how to make a Miller Act claim for unpaid federal subcontractor invoices.

When making a Miller Act claim against a payment bond on a federal project, the first step is to deliver a claim notice to the Prime Contractor.

This is different from a Preliminary Notice because the payment claim notice is the actual notification to the Prime Contractor that you will be making a claim, unlike the Preliminary Notice which secures your right to file a mechanics lien.

Per the Miller Act’s § 3133, the notice “must state with substantial accuracy the amount claimed and the name of the party to whom the material was furnished or supplied or for whom the labor was done or performed.”

The law doesn’t provide a fixed format via a statutory form for Miller Act claim notices. You can deliver a Miller Act claim notice with us at Handle to ensure that it’s valid and accurate.

It’s crucial that the claim notice to the Prime Contractor is delivered via a method that gives you proof of delivery. You can send it via certified mail with return receipt requested, but the law also allows the Miller Act claim notice to be delivered “(A) by any means that provides written, third-party verification of delivery.”

Although this is not a hard requirement, it is essential to send a copy of the Miller Act claim notice to the surety make sure that your claim gets as much attention as soon as possible.

Consistent with the law’s stance that the government must be kept out of disagreements and disputes between the Prime Contractor and federal subcontractors, you don’t need to notify the federal agency or contracting officer of the bond claim under the US Miller Act. It’s worth noting that the same thing applies to the surety: You don’t need to send them a notice. The responsibility of notifying the surety solely lies on the Prime Contractor.

To be sure, the next best step is to find out if the Primer Contractor did forward your notice to the surety in some way. You have to verify that they know that you’re claiming against the bond.

It’s crucial that you contact the surety even if it’s not your responsibility to notify them of a claim because part of making a successful claim is sending a sworn claim form and claim backup to the surety. All sureties and bonding companies require these two to process claims.

Sending a copy of the Miller Act claim notice at the same time or right after you send the notice to the Prime Contractor will ensure you’re not wasting time. The challenge here is finding out for sure who the surety your Prime Contractor used. The contracting officer for the federal project has the responsibility under the US Miller Act to tell you this information once you’ve requested it.

Once you’ve sent the notice to the surety, make sure to get a form of confirmation that they have received it via certified mail with receipt or hand delivery.

The next step to start the claims process is to send the surety a sworn claim form and a claim backup. There is no statutory form for this, but each bonding company or surety has their claim forms.

They will provide the claim form to you along with a request to provide information and documents that backup your claim. This is why it’s absolutely essential to keep all records including receipts, invoices, official correspondences between you and the prime contractor or other subcontractors, orders, the official contract, vouchers, and other documents that will back up and prove your claim.

Since it usually takes a surety a long time (more than a month) to review claims, make sure you send these documents as early as possible. Organize the documents neatly and send them to the surety along with the signed (and often, notarized as required) claim form.

This gets the process of their verification of your claim.

Do not forget to keep your copies.

After sending the claim notice to the Prime Contractor and the Surety (along with the form and documents), the waiting game starts. When you’re waiting on money that’s owed to you, this can feel like a very long time. It usually takes sureties a month to a month and a half to review and return your documents.

The claim decision comes with the return of the documents. The surety will have decided if they will pay or reject your Miller Act bond claim.

Most bond claims are settled with Step 3, but it’s normal to have to file a lawsuit in case the claim is not approved by the surety. As the claimant, you need to enforce the claim using the Miller Act. The only way to do this is via filing a lawsuit.

There is no definite deadline stated in law for the enforcement lawsuit of your Miller Act claim. However, there are guidelines:

Since there’s no definite deadline as to when you should file the lawsuit, it’s a case-to-case basis. It’s always better not to escalate the issue to a lawsuit. Keeping the deadlines in mind, try your best to get in touch with the Prime Contractor to make the situation right.

The waiting times between each step is always an opportunity for you and the Prime Contractor to discuss and settle the dispute.

Keep the 1-year deadline in mind and file the lawsuit if your out-of-court discussions are not getting anywhere. As soon as you deem that there is no progress being made toward resolution, pull the trigger and file the lawsuit in federal district court.

After a year, you lose all your rights to the claim, so stay on top of it.

Your claim enforcement lawsuit must be filed in the federal district court where the federal project is located. Your location, the surety’s location, and the Prime Contractor’s location don’t matter. Under the US Miller Act, the lawsuit must be filed in the federal district court where the construction site is located.

Technically, an enforcement lawsuit is not you suing the Prime Contractor. Enforcing a Miller Act claim is bringing a suit against the payment bond. Because of this, the bonding company or the surety is the party that needs to be named on the lawsuit.

You might also need to name the Prime Contractor as they are the party that secured the bond with the surety (bond beneficiary), but in most cases, this is not necessary.

What’s more important to note is that the United States will be named on your behalf ( the claimant-subcontractor) to bring the Miller Act claim enforcement suit.

(a)Definition.—

In this subchapter, the term “contractor” means a person awarded a contract described in subsection (b).

(b)Type of Bonds Required.—Before any contract of more than $100,000 is awarded for the construction, alteration, or repair of any public building or public work of the Federal Government; a person must furnish to the Government the following bonds, which become binding when the contract is awarded:

(1)Performance bond.—

A performance bond with a surety satisfactory to the officer awarding the contract, and in an amount the officer considers adequate, for the protection of the Government.

(2)Payment bond.—

A payment bond with a surety satisfactory to the officer for the protection of all persons supplying labor and material in carrying out the work provided for in the contract for the use of each person. The amount of the payment bond shall equal the total amount payable by the terms of the contract unless the officer awarding the contract determines, in a writing supported by specific findings, that a payment bond in that amount is impractical, in which case the contracting officer shall set the amount of the payment bond. The amount of the payment bond shall not be less than the amount of the performance bond.

(c) Coverage for Taxes in Performance Bond.—

(1)In general.—

Every performance bond required under this section specifically shall provide coverage for taxes the Government imposes which are collected, deducted, or withheld from wages the contractor pays in carrying out the contract with respect to which the bond is furnished.

(2)Notice.—

The Government shall give the surety on the bond written notice, with respect to any unpaid taxes attributable to any period, within 90 days after the date when the contractor files a return for the period, except that notice must be given no later than 180 days from the date when a return for the period was required to be filed under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (26 U.S.C. 1 et seq.).

(3)Civil action.—The Government may not bring a civil action on the bond for the taxes—

(A) unless notice is given as provided in this subsection; and

(B) more than one year after the day on which notice is given.

(d)Waiver of Bonds for Contracts Performed in Foreign Countries.—

A contracting officer may waive the requirement of a performance bond and payment bond for work under a contract that is to be performed in a foreign country if the officer finds that it is impracticable for the contractor to furnish the bonds.

(e)Authority To Require Additional Bonds.—

This section does not limit the authority of a contracting officer to require a performance bond or other security in addition to those, or in cases other than the cases, specified in subsection (b).

(Pub. L. 107–217, Aug. 21, 2002, 116 Stat. 1147; Pub. L. 109–284, § 6(8), Sept. 27, 2006, 120 Stat. 1213.)

It’s important that you know your rights as a subcontractor entering a federal project. When payments issue arise, your interests will be best protected if you act fast.

The possibility of losing your rights to the payment bond claim in case of a payment issue is very real, especially when you don’t know what to do first. The process may be easy, but the finer details must never be skipped or overlooked as it can cost you thousands of dollars. You can also opt to make your Miller Act claim through Handle to make the process error-free and secure.